Preface

As more critical aspects of our lives become dependant on software systems, more and more applications are required to save the data they work on in persistent and reliable storage. Database management systems and, in particular, relational database management systems (RDBMS) are commonly used for such storage. However, while the application development techniques and programming languages have evolved significantly over the past decades, the relational database technology in this area stayed relatively unchanged. In particular, this led to the now infamous mismatch between the object-oriented model used by many modern applications and the relational model still used by RDBMS.

While relational databases may be inconvenient to use from modern programming languages, they are still the main choice for many applications due to their maturity, reliability, as well as the availability of tools and alternative implementations.

To allow application developers to utilize relational databases from their object-oriented applications, a technique called object-relational mapping (ORM) is often used. It involves a conversion layer that maps between objects in the application's memory and their relational representation in the database. While the object-relational mapping code can be written manually, automated ORM systems are available for most object-oriented programming languages in use today.

ODB is an ORM system for the C++ programming language. It was designed and implemented with the following main goals:

- Provide a fully-automatic ORM system. In particular, the application developer should not have to manually write any mapping code, neither for persistent classes nor for their data member.

- Provide clean and easy to use object-oriented persistence model and database APIs that support the development of realistic applications for a wide variety of domains.

- Provide a portable and thread-safe implementation. ODB should be written in standard C++ and capable of persisting any standard C++ classes.

- Provide profiles that integrate ODB with type systems of widely-used frameworks and libraries such as Qt and Boost.

- Provide a high-performance and low overhead implementation. ODB should make efficient use of database and application resources.

About This Document

The goal of this manual is to provide you with an understanding of the object persistence model and APIs which are implemented by ODB. As such, this document is intended for C++ application developers and software architects who are looking for a C++ object persistence solution. Prior experience with C++ is required to understand this document. A basic understanding of relational database systems is advantageous but not expected or required.

More Information

Beyond this manual, you may also find the following sources of information useful:

- ODB Compiler Command Line Manual.

- The

INSTALLfiles in the ODB source packages provide build instructions for various platforms. - The

odb-examplespackage contains a collection of examples and a README file with an overview of each example. - The odb-users mailing list is the place to ask technical questions about ODB. Furthermore, the searchable archives may already have answers to some of your questions.

PART I OBJECT-RELATIONAL MAPPING

Part I describes the essential database concepts, APIs, and tools that together comprise the object-relational mapping for C++ as implemented by ODB. It consists of the following chapters.

1 Introduction

ODB is an object-relational mapping (ORM) system for C++. It provides tools, APIs, and library support that allow you to persist C++ objects to a relational database (RDBMS) without having to deal with tables, columns, or SQL and without manually writing any of the mapping code.

ODB is highly flexible and customizable. It can either completely

hide the relational nature of the underlying database or expose

some of the details as required. For example, you can automatically

map basic C++ types to suitable SQL types, generate the relational

database schema for your persistent classes, and use simple, safe,

and yet powerful object query language instead of SQL. Or you can

assign SQL types to individual data members, use the existing

database schema, run native SQL SELECT queries, and

call stored procedures. In fact, at an extreme, ODB can be used

as just a convenient way to handle results of native SQL

queries.

ODB is not a framework. It does not dictate how you should write your application. Rather, it is designed to fit into your style and architecture by only handling object persistence and not interfering with any other functionality. There is no common base type that all persistent classes should derive from nor are there any restrictions on the data member types in persistent classes. Existing classes can be made persistent with a few or no modifications.

ODB has been designed for high performance and low memory overhead. Prepared statements are used to send and receive object state in binary format instead of text which reduces the load on the application and the database server. Extensive caching of connections, prepared statements, and buffers saves time and resources on connection establishment, statement parsing, and memory allocations. For each supported database system the native C API is used instead of ODBC or higher-level wrapper APIs to reduce overhead and provide the most efficient implementation for each database operation. Finally, persistent classes have zero memory overhead. There are no hidden "database" members that each class must have nor are there per-object data structures allocated by ODB.

In this chapter we present a high-level overview of ODB. We will start with the ODB architecture and then outline the workflow of building an application that uses ODB. We will then continue by contrasting the drawbacks of the traditional way of saving C++ objects to relational databases with the benefits of using ODB for object persistence. We conclude the chapter by discussing the C++ standards supported by ODB. The next chapter takes a more hands-on approach and shows the concrete steps necessary to implement object persistence in a simple "Hello World" application.

1.1 Architecture and Workflow

From the application developer's perspective, ODB

consists of three main components: the ODB compiler, the common

runtime library, called libodb, and the

database-specific runtime libraries, called

libodb-<database>, where <database> is

the name of the database system this runtime

is for, for example, libodb-mysql. For instance,

if the application is going to use the MySQL database for

object persistence, then the three ODB components that this

application will use are the ODB compiler, libodb

and libodb-mysql.

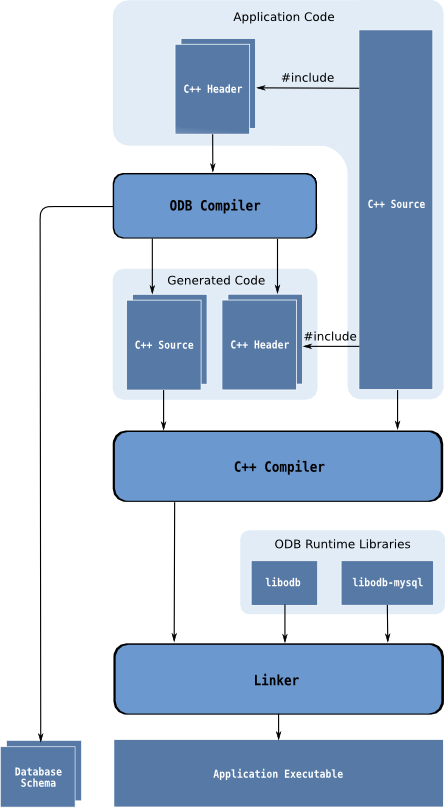

The ODB compiler generates the database support code for persistent classes in your application. The input to the ODB compiler is one or more C++ header files defining C++ classes that you want to make persistent. For each input header file the ODB compiler generates a set of C++ source files implementing conversion between persistent C++ classes defined in this header and their database representation. The ODB compiler can also generate a database schema file that creates tables necessary to store the persistent classes.

The ODB compiler is a real C++ compiler except that it produces C++ instead of assembly or machine code. In particular, it is not an ad-hoc header pre-processor that is only capable of recognizing a subset of C++. ODB is capable of parsing any standard C++ code.

The common runtime library defines database system-independent

interfaces that your application can use to manipulate persistent

objects. The database-specific runtime library provides implementations

of these interfaces for a concrete database as well as other

database-specific utilities that are used by the generated code.

Normally, the application does not use the database-specific

runtime library directly but rather works with it via the common

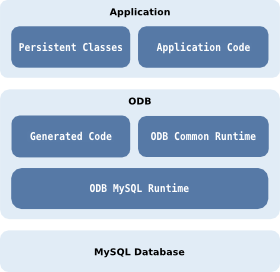

interfaces from libodb. The following diagram shows

the object persistence architecture of an application that uses

MySQL as the underlying database system:

The ODB system also defines two special-purpose languages:

the ODB Pragma Language and ODB Query Language. The ODB Pragma

Language is used to communicate various properties of persistent

classes to the ODB compiler by means of special #pragma

directives embedded in the C++ header files. It controls aspects

of the object-relational mapping such as names of tables and columns

that are used for persistent classes and their members or mapping between

C++ types and database types.

The ODB Query Language is an object-oriented database query language that can be used to search for objects matching certain criteria. It is modeled after and is integrated into C++ allowing you to write expressive and safe queries that look and feel like ordinary C++.

The use of the ODB compiler to generate database support code adds an additional step to your application build sequence. The following diagram outlines the typical build workflow of an application that uses ODB:

1.2 Benefits

The traditional way of saving C++ objects to relational databases requires that you manually write code which converts between the database and C++ representations of each persistent class. The actions that such code usually performs include conversion between C++ values and strings or database types, preparation and execution of SQL queries, as well as handling the result sets. Writing this code manually has the following drawbacks:

- Difficult and time consuming. Writing database conversion code for any non-trivial application requires extensive knowledge of the specific database system and its APIs. It can also take a considerable amount of time to write and maintain. Supporting multi-threaded applications can complicate this task even further.

- Suboptimal performance. Optimal conversion often requires writing large amounts of extra code, such as parameter binding for prepared statements and caching of connections, statements, and buffers. Writing code like this in an ad-hoc manner is often too difficult and time consuming.

- Database vendor lock-in. The conversion code is written for a specific database which makes it hard to switch to another database vendor.

- Lack of type safety. It is easy to misspell column names or pass incompatible values in SQL queries. Such errors will only be detected at runtime.

- Complicates the application. The database conversion code often ends up interspersed throughout the application making it hard to debug, change, and maintain.

In contrast, using ODB for C++ object persistence has the following benefits:

- Ease of use. ODB automatically generates database conversion code from your C++ class declarations and allows you to manipulate persistent objects using simple and thread-safe object-oriented database APIs.

- Concise code. With ODB hiding the details of the underlying database, the application logic is written using the natural object vocabulary instead of tables, columns and SQL. The resulting code is simpler and thus easier to read and understand.

- Optimal performance. ODB has been designed for high performance and low memory overhead. All the available optimization techniques, such as prepared statements and extensive connection, statement, and buffer caching, are used to provide the most efficient implementation for each database operation.

- Database portability. Because the database conversion code is automatically generated, it is easy to switch from one database vendor to another. In fact, it is possible to test your application on several database systems before making a choice.

- Safety. The ODB object persistence and query APIs are statically typed. You use C++ identifiers instead of strings to refer to object members and the generated code makes sure database and C++ types are compatible. All this helps catch programming errors at compile-time rather than at runtime.

- Maintainability. Automatic code generation minimizes the effort needed to adapt the application to changes in persistent classes. The database support code is kept separately from the class declarations and application logic. This makes the application easier to debug and maintain.

Overall, ODB provides an easy to use yet flexible and powerful object-relational mapping (ORM) system for C++. Unlike other ORM implementations for C++ that still require you to write database conversion or member registration code for each persistent class, ODB keeps persistent classes purely declarative. The functional part, the database conversion code, is automatically generated by the ODB compiler from these declarations.

1.3 Supported C++ Standards

ODB provides support for ISO/IEC C++ 1998/2003 (C++98/03), ISO/IEC C++

2011 (C++11), as well later standards with the majority of the examples

in this manual using C++11. The c++11 example in the

odb-examples package shows ODB support for various

features new in C++11.

2 Hello World Example

In this chapter we will show how to create a simple C++ application that relies on ODB for object persistence using the traditional "Hello World" example. In particular, we will discuss how to declare persistent classes, generate database support code, as well as compile and run our application. We will also learn how to make objects persistent, load, update and delete persistent objects, as well as query the database for persistent objects that match certain criteria. The example also shows how to define and use views, a mechanism that allows us to create projections of persistent objects, database tables, or to handle results of native SQL queries or stored procedure calls.

The code presented in this chapter is based on the

hello example which can be found in the

odb-examples package of the ODB distribution.

2.1 Declaring Persistent Classes

In our "Hello World" example we will depart slightly from

the norm and say hello to people instead of the world. People

in our application will be represented as objects of C++ class

person which is saved in person.hxx:

// person.hxx

//

#include <string>

class person

{

public:

person (const std::string& first,

const std::string& last,

unsigned short age);

const std::string& first () const;

const std::string& last () const;

unsigned short age () const;

void age (unsigned short);

private:

std::string first_;

std::string last_;

unsigned short age_;

};

In order not to miss anyone whom we need to greet, we would like

to save the person objects in a database. To achieve this

we declare the person class as persistent:

// person.hxx

//

#include <string>

#include <odb/core.hxx> // (1)

#pragma db object // (2)

class person

{

...

private:

person () {} // (3)

friend class odb::access; // (4)

#pragma db id auto // (5)

unsigned long long id_; // (5)

std::string first_;

std::string last_;

unsigned short age_;

};

To be able to save the person objects in the database

we had to make five changes, marked with (1) to (5), to the original

class definition. The first change is the inclusion of the ODB

header <odb/core.hxx>. This header provides a number

of core ODB declarations, such as odb::access, that

are used to define persistent classes.

The second change is the addition of db object

pragma just before the class definition. This pragma tells the

ODB compiler that the class that follows is persistent. Note

that making a class persistent does not mean that all objects

of this class will automatically be stored in the database.

You would still create ordinary or transient instances

of this class just as you would before. The difference is that

now you can make such transient instances persistent, as we will

see shortly.

The third change is the addition of the default constructor.

The ODB-generated database support code will use this constructor

when instantiating an object from the persistent state. Just as we have

done for the person class, you can make the default

constructor private or protected if you don't want to make it

available to the users of your class. Note also that with some

limitations it is possible to have a persistent class without

the default constructor.

With the fourth change we make the odb::access class a

friend of our person class. This is necessary to make

the default constructor and the data members accessible to the

database support code. If your class has a public default constructor and

either public data members or public accessors and modifiers for the

data members, then the friend declaration is unnecessary.

The final change adds a data member called id_ which

is preceded by another pragma. In ODB every persistent object normally

has a unique, within its class, identifier. Or, in other words, no two

persistent instances of the same type have equal identifiers. While it

is possible to define a persistent class without an object id, the number

of database operations that can be performed on such a class is limited.

For our class we use an integer id. The db id auto

pragma that precedes the id_ member tells the ODB compiler

that the following member is the object's identifier. The

auto specifier indicates that it is a database-assigned

id. A unique id will be automatically generated by the database and

assigned to the object when it is made persistent.

In this example we chose to add an identifier because none of

the existing members could serve the same purpose. However, if

a class already has a member with suitable properties, then it

is natural to use that member as an identifier. For example,

if our person class contained some form of personal

identification (SSN in the United States or ID/passport number

in other countries), then we could use that as an id. Or, if

we stored an email associated with each person, then we could

have used that if each person is presumed to have a unique

email address.

As another example, consider the following alternative version

of the person class. Here we use one of

the existing data members as id. Also the data members are kept

private and are instead accessed via public accessor and modifier

functions. Finally, the ODB pragmas are grouped together and are

placed after the class definition. They could have also been moved

into a separate header leaving the original class completely

unchanged (for more information on such a non-intrusive conversion

refer to Chapter 14, "ODB Pragma Language").

class person

{

public:

person ();

const std::string& email () const;

void email (const std::string&);

const std::string& get_name () const;

std::string& set_name ();

unsigned short getAge () const;

void setAge (unsigned short);

private:

std::string email_;

std::string name_;

unsigned short age_;

};

#pragma db object(person)

#pragma db member(person::email_) id

Now that we have the header file with the persistent class, let's see how we can generate that database support code.

2.2 Generating Database Support Code

The persistent class definition that we created in the previous section was particularly light on any code that could actually do the job and store the person's data to a database. There was no serialization or deserialization code, not even data member registration, that you would normally have to write by hand in other ORM libraries for C++. This is because in ODB code that translates between the database and C++ representations of an object is automatically generated by the ODB compiler.

To compile the person.hxx header we created in the

previous section and generate the support code for the MySQL

database, we invoke the ODB compiler from a terminal (UNIX) or

a command prompt (Windows):

odb -d mysql --generate-query person.hxx

We will use MySQL as the database of choice in the remainder of this chapter, though other supported database systems can be used instead.

If you haven't installed the common ODB runtime library

(libodb) or installed it into a directory where

C++ compilers don't search for headers by default,

then you may get the following error:

person.hxx:10:24: fatal error: odb/core.hxx: No such file or directory

To resolve this you will need to specify the libodb headers

location with the -I preprocessor option, for example:

odb -I.../libodb -d mysql --generate-query person.hxx

Here .../libodb represents the path to the

libodb directory.

The above invocation of the ODB compiler produces three C++ files:

person-odb.hxx, person-odb.ixx,

person-odb.cxx. You normally don't use types

or functions contained in these files directly. Rather, all

you have to do is include person-odb.hxx in

C++ files where you are performing database operations

with classes from person.hxx as well as compile

person-odb.cxx and link the resulting object

file to your application.

You may be wondering what the --generate-query

option is for. It instructs the ODB compiler to generate

optional query support code that we will use later in our

"Hello World" example. Another option that we will find

useful is --generate-schema. This option

makes the ODB compiler generate a fourth file,

person.sql, which is the database schema

for the persistent classes defined in person.hxx:

odb -d mysql --generate-query --generate-schema person.hxx

The database schema file contains SQL statements that creates tables necessary to store the persistent classes. We will learn how to use it in the next section.

If you would like to see a list of all the available ODB compiler options, refer to the ODB Compiler Command Line Manual.

Now that we have the persistent class and the database support code, the only part that is left is the application code that does something useful with all of this. But before we move on to the fun part, let's first learn how to build and run an application that uses ODB. This way when we have some application code to try, there are no more delays before we can run it.

2.3 Compiling and Running

Assuming that the main() function with the application

code is saved in driver.cxx and the database support

code and schema are generated as described in the previous section,

to build our application we will first need to compile all the C++

source files and then link them with two ODB runtime libraries.

On UNIX, the compilation part can be done with the following commands

(substitute c++ with your C++ compiler name; for Microsoft

Visual Studio setup, see the odb-examples package):

c++ -c driver.cxx c++ -c person-odb.cxx

Similar to the ODB compilation, if you get an error stating that

a header in odb/ or odb/mysql directory

is not found, you will need to use the -I

preprocessor option to specify the location of the common ODB runtime

library (libodb) and MySQL ODB runtime library

(libodb-mysql).

Once the compilation is done, we can link the application with the following command:

c++ -o driver driver.o person-odb.o -lodb-mysql -lodb

Notice that we link our application with two ODB libraries:

libodb which is a common runtime library and

libodb-mysql which is a MySQL runtime library

(if you use another database, then the name of this library

will change accordingly). If you get an error saying that

one of these libraries could not be found, then you will need

to use the -L linker option to specify their locations.

Before we can run our application we need to create a database

schema using the generated person.sql file. For MySQL

we can use the mysql client program, for example:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person.sql

The above command will log in to a local MySQL server as user

odb_test without a password and use the database

named odb_test. Beware that after executing this

command, all the data stored in the odb_test database

will be deleted.

Note also that using a standalone generated SQL file is not the only way to create a database schema in ODB. We can also embed the schema directly into our application or use custom schemas that were not generated by the ODB compiler. Refer to Section 3.4, "Database" for details.

Once the database schema is ready, we run our application using the same login and database name:

./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test

2.4 Making Objects Persistent

Now that we have the infrastructure work out of the way, it

is time to see our first code fragment that interacts with the

database. In this section we will learn how to make person

objects persistent:

// driver.cxx

//

#include <memory> // std::unique_ptr

#include <iostream>

#include <odb/database.hxx>

#include <odb/transaction.hxx>

#include <odb/mysql/database.hxx>

#include "person.hxx"

#include "person-odb.hxx"

using namespace std;

using namespace odb::core;

int

main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

try

{

unique_ptr<database> db (new odb::mysql::database (argc, argv));

unsigned long long john_id, jane_id, joe_id;

// Create a few persistent person objects.

//

{

person john ("John", "Doe", 33);

person jane ("Jane", "Doe", 32);

person joe ("Joe", "Dirt", 30);

transaction t (db->begin ());

// Make objects persistent and save their ids for later use.

//

john_id = db->persist (john);

jane_id = db->persist (jane);

joe_id = db->persist (joe);

t.commit ();

}

}

catch (const odb::exception& e)

{

cerr << e.what () << endl;

return 1;

}

}

Let's examine this code piece by piece. At the beginning we include

a bunch of headers. After the standard C++ headers we include

<odb/database.hxx>

and <odb/transaction.hxx> which define database

system-independent odb::database and

odb::transaction interfaces. Then we include

<odb/mysql/database.hxx> which defines the

MySQL implementation of the database interface. Finally,

we include person.hxx and person-odb.hxx

which define our persistent person class.

Then we have two using namespace directives. The first

one brings in the names from the standard namespace and the second

brings in the ODB declarations which we will use later in the file.

Notice that in the second directive we use the odb::core

namespace instead of just odb. The former only brings

into the current namespace the essential ODB names, such as the

database and transaction classes, without

any of the auxiliary objects. This minimizes the likelihood of name

conflicts with other libraries. Note also that you should continue

using the odb namespace when qualifying individual names.

For example, you should write odb::database, not

odb::core::database.

Once we are in main(), the first thing we do is create

the MySQL database object. Notice that this is the last line in

driver.cxx that mentions MySQL explicitly; the rest

of the code works through the common interfaces and is database

system-independent. We use the argc/argv

mysql::database constructor which automatically

extract the database parameters, such as login name, password,

database name, etc., from the command line. In your own applications

you may prefer to use other mysql::database

constructors which allow you to pass this information directly

(Section 17.2, "MySQL Database Class").

Next, we create three person objects. Right now they are

transient objects, which means that if we terminate the application

at this point, they will be gone without any evidence of them ever

existing. The next line starts a database transaction. We discuss

transactions in detail later in this manual. For now, all we need

to know is that all ODB database operations must be performed within

a transaction and that a transaction is an atomic unit of work; all

database operations performed within a transaction either succeed

(committed) together or are automatically undone (rolled back).

Once we are in a transaction, we call the persist()

database function on each of our person objects.

At this point the state of each object is saved in the database.

However, note that this state is not permanent until and unless

the transaction is committed. If, for example, our application

crashes at this point, there will still be no evidence of our

objects ever existing.

In our case, one more thing happens when we call persist().

Remember that we decided to use database-assigned identifiers for our

person objects. The call to persist() is

where this assignment happens. Once this function returns, the

id_ member contains this object's unique identifier.

As a convenience, the persist() function also returns

a copy of the object's identifier that it made persistent. We

save the returned identifier for each object in a local variable.

We will use these identifiers later in the chapter to perform other

database operations on our persistent objects.

After we have persisted our objects, it is time to commit the

transaction and make the changes permanent. Only after the

commit() function returns successfully, are we

guaranteed that the objects are made persistent. Continuing

with the crash example, if our application terminates after

the commit for whatever reason, the objects' state in the

database will remain intact. In fact, as we will discover

shortly, our application can be restarted and load the

original objects from the database. Note also that a

transaction must be committed explicitly with the

commit() call. If the transaction

object leaves scope without the transaction being

explicitly committed or rolled back, it will automatically be

rolled back. This behavior allows you not to worry about

exceptions being thrown within a transaction; if they

cross the transaction boundary, the transaction will

automatically be rolled back and all the changes made

to the database undone.

The final bit of code in our example is the catch

block that handles the database exceptions. We do this by catching

the base ODB exception (Section 3.14, "ODB

Exceptions") and printing the diagnostics.

Let's now compile (Section 2.3, "Compiling and Running") and then run our first ODB application:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person.sql ./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test

Our first application doesn't print anything except for error

messages so we can't really tell whether it actually stored the

objects' state in the database. While we will make our application

more entertaining shortly, for now we can use the mysql

client to examine the database content. It will also give us a feel

for how the objects are stored:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test Welcome to the MySQL monitor. mysql> select * from person; +----+-------+------+-----+ | id | first | last | age | +----+-------+------+-----+ | 1 | John | Doe | 33 | | 2 | Jane | Doe | 32 | | 3 | Joe | Dirt | 30 | +----+-------+------+-----+ 3 rows in set (0.00 sec) mysql> quit

Another way to get more insight into what's going on under the hood, is to trace the SQL statements executed by ODB as a result of each database operation. Here is how we can enable tracing just for the duration of our transaction:

// Create a few persistent person objects.

//

{

...

transaction t (db->begin ());

t.tracer (stderr_tracer);

// Make objects persistent and save their ids for later use.

//

john_id = db->persist (john);

jane_id = db->persist (jane);

joe_id = db->persist (joe);

t.commit ();

}

With this modification our application now produces the following output:

INSERT INTO `person` (`id`,`first`,`last`,`age`) VALUES (?,?,?,?) INSERT INTO `person` (`id`,`first`,`last`,`age`) VALUES (?,?,?,?) INSERT INTO `person` (`id`,`first`,`last`,`age`) VALUES (?,?,?,?)

Note that we see question marks instead of the actual values because ODB uses prepared statements and sends the data to the database in binary form. For more information on tracing, refer to Section 3.13, "Tracing SQL Statement Execution". In the next section we will see how to access persistent objects from our application.

2.5 Querying the Database for Objects

So far our application doesn't resemble a typical "Hello World" example. It doesn't print anything except for error messages. Let's change that and teach our application to say hello to people from our database. To make it a bit more interesting, let's say hello only to people over 30:

// driver.cxx

//

...

int

main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

try

{

...

// Create a few persistent person objects.

//

{

...

}

using query = odb::query<person>;

using result = odb::result<person>;

// Say hello to those over 30.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

result r (db->query<person> (query::age > 30));

for (result::iterator i (r.begin ()); i != r.end (); ++i)

{

cout << "Hello, " << i->first () << "!" << endl;

}

t.commit ();

}

}

catch (const odb::exception& e)

{

cerr << e.what () << endl;

return 1;

}

}

The first half of our application is the same as before and is replaced with "..." in the above listing for brevity. Again, let's examine the rest of it piece by piece.

The two using declarations create convenient aliases for two

template instantiations that will be used a lot in our application. The

first is the query type for the person objects and the

second is the result type for that query.

Then we begin a new transaction and call the query()

database function. We pass a query expression

(query::age > 30) which limits the returned objects

only to those with the age greater than 30. We also save the result

of the query in a local variable.

The next few lines perform a standard for-loop iteration over the result sequence printing hello for every returned person. Then we commit the transaction and that's it. Let's see what this application will print:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person.sql ./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test Hello, John! Hello, Jane!

That looks about right, but how do we know that the query actually

used the database instead of just using some in-memory artifacts of

the earlier persist() calls? One way to test this

would be to comment out the first transaction in our application

and re-run it without re-creating the database schema. This way the

objects that were persisted during the previous run will be returned.

Alternatively, we can just re-run the same application without

re-creating the schema and notice that we now show duplicate

objects:

./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test Hello, John! Hello, Jane! Hello, John! Hello, Jane!

What happens here is that the previous run of our application

persisted a set of person objects and when we re-run

the application, we persist another set with the same names but

with different ids. When we later run the query, matches from

both sets are returned. We can change the line where we print

the "Hello" string as follows to illustrate this point:

cout << "Hello, " << i->first () << " (" << i->id () << ")!" << endl;

If we now re-run this modified program, again without re-creating the database schema, we will get the following output:

./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test Hello, John (1)! Hello, Jane (2)! Hello, John (4)! Hello, Jane (5)! Hello, John (7)! Hello, Jane (8)!

The identifiers 3, 6, and 9 that are missing from the above list belong to the "Joe Dirt" objects which are not selected by this query.

2.6 Updating Persistent Objects

While making objects persistent and then selecting some of them using queries are two useful operations, most applications will also need to change the object's state and then make these changes persistent. Let's illustrate this by updating Joe's age who just had a birthday:

// driver.cxx

//

...

int

main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

try

{

...

unsigned long long john_id, jane_id, joe_id;

// Create a few persistent person objects.

//

{

...

// Save object ids for later use.

//

john_id = john.id ();

jane_id = jane.id ();

joe_id = joe.id ();

}

// Joe Dirt just had a birthday, so update his age.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

unique_ptr<person> joe (db->load<person> (joe_id));

joe->age (joe->age () + 1);

db->update (*joe);

t.commit ();

}

// Say hello to those over 30.

//

{

...

}

}

catch (const odb::exception& e)

{

cerr << e.what () << endl;

return 1;

}

}

The beginning and the end of the new transaction are the same as

the previous two. Once within a transaction, we call the

load() database function to instantiate a

person object with Joe's persistent state. We

pass Joe's object identifier that we stored earlier when we

made this object persistent. While here we use

std::unique_ptr to manage the returned object, we

could have also used another smart pointer, for example

shared_ptr from C++11 or Boost. For more information on the

object lifetime management and the smart pointers that we can use for

that, see Section 3.3, "Object and View Pointers".

With the instantiated object in hand we increment the age

and call the update() function to update

the object's state in the database. Once the transaction is

committed, the changes are made permanent.

If we now run this application, we will see Joe in the output since he is now over 30:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person.sql ./driver --user odb_test --database odb_test Hello, John! Hello, Jane! Hello, Joe!

What if we didn't have an identifier for Joe? Maybe this object was made persistent in another run of our application or by another application altogether. Provided that we only have one Joe Dirt in the database, we can use the query facility to come up with an alternative implementation of the above transaction:

// Joe Dirt just had a birthday, so update his age. An

// alternative implementation without using the object id.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

// Here we know that there can be only one Joe Dirt in our

// database so we use the query_one() shortcut instead of

// manually iterating over the result returned by query().

//

unique_ptr<person> joe (

db->query_one<person> (query::first == "Joe" &&

query::last == "Dirt"));

if (joe.get () != 0)

{

joe->age (joe->age () + 1);

db->update (*joe);

}

t.commit ();

}

2.7 Defining and Using Views

Suppose that we need to gather some basic statistics about the people

stored in our database. Things like the total head count, as well as

the minimum and maximum ages. One way to do it would be to query

the database for all the person objects and then

calculate this information as we iterate over the query result.

While this approach may work fine for our database with just three

people in it, it would be very inefficient if we had a large

number of objects.

While it may not be conceptually pure from the object-oriented programming point of view, a relational database can perform some computations much faster and much more economically than if we performed the same operations ourselves in the application's process.

To support such cases ODB provides the notion of views. An ODB view

is a C++ class that embodies a light-weight, read-only

projection of one or more persistent objects or database tables or

the result of a native SQL query execution or stored procedure

call.

Some of the common applications of views include loading a subset of data members from objects or columns database tables, executing and handling results of arbitrary SQL queries, including aggregate queries, as well as joining multiple objects and/or database tables using object relationships or custom join conditions.

While you can find a much more detailed description of views in

Chapter 10, "Views", here is how we can define

the person_stat view that returns the basic statistics

about the person objects:

#pragma db view object(person)

struct person_stat

{

#pragma db column("count(" + person::id_ + ")")

std::size_t count;

#pragma db column("min(" + person::age_ + ")")

unsigned short min_age;

#pragma db column("max(" + person::age_ + ")")

unsigned short max_age;

};

Normally, to get the result of a view we use the same

query() function as when querying the database for

an object. Here, however, we are executing an aggregate query

which always returns exactly one element. Therefore, instead

of getting the result instance and then iterating over it, we

can use the shortcut query_value() function. Here is

how we can load and print our statistics using the view we have

just created:

// Print some statistics about all the people in our database.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

// The result of this query always has exactly one element.

//

person_stat ps (db->query_value<person_stat> ());

cout << "count : " << ps.count << endl

<< "min age: " << ps.min_age << endl

<< "max age: " << ps.max_age << endl;

t.commit ();

}

If we now add the person_stat view to the

person.hxx header, the above transaction

to driver.cxx, as well as re-compile and

re-run our example, then we will see the following

additional lines in the output:

count : 3 min age: 31 max age: 33

2.8 Deleting Persistent Objects

The last operation that we will discuss in this chapter is deleting the persistent object from the database. The following code fragment shows how we can delete an object given its identifier:

// John Doe is no longer in our database.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

db->erase<person> (john_id);

t.commit ();

}

To delete John from the database we start a transaction, call

the erase() database function with John's object

id, and commit the transaction. After the transaction is committed,

the erased object is no longer persistent.

If we don't have an object id handy, we can use queries to find and delete the object:

// John Doe is no longer in our database. An alternative

// implementation without using the object id.

//

{

transaction t (db->begin ());

// Here we know that there can be only one John Doe in our

// database so we use the query_one() shortcut again.

//

unique_ptr<person> john (

db->query_one<person> (query::first == "John" &&

query::last == "Doe"));

if (john.get () != 0)

db->erase (*john);

t.commit ();

}

2.9 Changing Persistent Classes

When the definition of a transient C++ class is changed, for example by adding or deleting a data member, we don't have to worry about any existing instances of this class not matching the new definition. After all, to make the class changes effective we have to restart the application and none of the transient instances will survive this.

Things are not as simple for persistent classes. Because they are stored in the database and therefore survive application restarts, we have a new problem: what happens to the state of existing objects (which correspond to the old definition) once we change our persistent class?

The problem of working with old objects, called database schema evolution, is a complex issue and ODB provides comprehensive support for handling it. While this support is covered in detail in Chapter 13, "Database Schema Evolution", let us consider a simple example that should give us a sense of the functionality provided by ODB in this area.

Suppose that after using our person persistent

class for some time and creating a number of databases

containing its instances, we realized that for some people

we also need to store their middle name. If we go ahead and

just add the new data member, everything will work fine

with new databases. Existing databases, however, have a

table that does not correspond to the new class definition.

Specifically, the generated database support code now

expects there to be a column to store the middle name.

But such a column was never created in the old databases.

ODB can automatically generate SQL statements that will migrate old databases to match the new class definitions. But first, we need to enable schema evolution support by defining a version for our object model:

// person.hxx

//

#pragma db model version(1, 1)

class person

{

...

std::string first_;

std::string last_;

unsigned short age_;

};

The first number in the version pragma is the

base model version. This is the lowest version we will be

able to migrate from. The second number is the current model

version. Since we haven't made any changes yet to our

persistent class, both of these values are 1.

Next we need to re-compile our person.hxx header

file with the ODB compiler, just as we did before:

odb -d mysql --generate-query --generate-schema person.hxx

If we now look at the list of files produced by the ODB compiler,

we will notice a new file: person.xml. This

is a changelog file where the ODB compiler keeps track of the

database changes corresponding to our class changes. Note that

this file is automatically maintained by the ODB compiler and

all we have to do is keep it around between re-compilations.

Now we are ready to add the middle name to our person

class. We also give it a default value (empty string) which

is what will be assigned to existing objects in old databases.

Notice that we have also incremented the current version:

// person.hxx

//

#pragma db model version(1, 2)

class person

{

...

std::string first_;

#pragma db default("")

std::string middle_;

std::string last_;

unsigned short age_;

};

If we now recompile the person.hxx header again, we will

see two extra generated files: person-002-pre.sql

and person-002-post.sql. These two files contain

schema migration statements from version 1 to

version 2. Similar to schema creation, schema

migration statements can also be embedded into the generated

C++ code.

person-002-pre.sql and person-002-post.sql

are the pre and post schema migration files. To migrate

one of our old databases, we first execute the pre migration

file:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person-002-pre.sql

Between the pre and post schema migrations we can run data migration code, if required. At this stage, we can both access the old and store the new data. In our case we don't need any data migration code since we assigned the default value to the middle name for all the existing objects.

To finish the migration process we execute the post migration statements:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person-002-post.sql

2.10 Working with Multiple Databases

Accessing multiple databases (that is, data stores) is simply a

matter of creating multiple odb::<db>::database

instances representing each database. For example:

odb::mysql::database db1 ("john", "secret", "test_db1");

odb::mysql::database db2 ("john", "secret", "test_db2");

Some database systems also allow attaching multiple databases to the same instance. A more interesting question is how we access multiple database systems (that is, database implementations) from the same application. For example, our application may need to store some objects in a remote MySQL database and others in a local SQLite file. Or, our application may need to be able to store its objects in a database system that is selected by the user at runtime.

ODB provides comprehensive multi-database support that ranges from tight integration with specific database systems to being able to write database-agnostic code and loading individual database systems support dynamically. While all these aspects are covered in detail in Chapter 16, "Multi-Database Support", in this section we will get a taste of this functionality by extending our "Hello World" example to be able to store its data either in MySQL or PostgreSQL (other database systems supported by ODB can be added in a similar manner).

The first step in adding multi-database support is to re-compile

our person.hxx header to generate database support

code for additional database systems:

odb --multi-database dynamic -d common -d mysql -d pgsql \ --generate-query --generate-schema person.hxx

The --multi-database ODB compiler option turns on

multi-database support. For now it is not important what the

dynamic value that we passed to this option means, but

if you are curious, see Chapter 16. The result of this

command are three sets of generated files: person-odb.?xx

(common interface; corresponds to the common database),

person-odb-mysql.?xx (MySQL support code), and

person-odb-pgsql.?xx (PostgreSQL support code). There

are also two schema files: person-mysql.sql and

person-pgsql.sql.

The only part that we need to change in driver.cxx

is how we create the database instance. Specifically, this line:

unique_ptr<database> db (new odb::mysql::database (argc, argv));

Now our example is capable of storing its data either in MySQL or

PostgreSQL so we need to somehow allow the caller to specify which

database we must use. To keep things simple, we will make the first

command line argument specify the database system we must use while

the rest will contain the database-specific options which we will

pass to the odb::<db>::database constructor as

before. Let's put all this logic into a separate function which we

will call create_database(). Here is what the beginning

of our modified driver.cxx will look like (the remainder

is unchanged):

// driver.cxx

//

#include <string>

#include <memory> // std::unique_ptr

#include <iostream>

#include <odb/database.hxx>

#include <odb/transaction.hxx>

#include <odb/mysql/database.hxx>

#include <odb/pgsql/database.hxx>

#include "person.hxx"

#include "person-odb.hxx"

using namespace std;

using namespace odb::core;

unique_ptr<database>

create_database (int argc, char* argv[])

{

unique_ptr<database> r;

if (argc < 2)

{

cerr << "error: database system name expected" << endl;

return r;

}

string db (argv[1]);

if (db == "mysql")

r.reset (new odb::mysql::database (argc, argv));

else if (db == "pgsql")

r.reset (new odb::pgsql::database (argc, argv));

else

cerr << "error: unknown database system " << db << endl;

return r;

}

int

main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

try

{

unique_ptr<database> db (create_database (argc, argv));

if (db.get () == 0)

return 1; // Diagnostics has already been issued.

...

And that's it. The only thing left is to build and run our example:

c++ -c driver.cxx c++ -c person-odb.cxx c++ -c person-odb-mysql.cxx c++ -c person-odb-pgsql.cxx c++ -o driver driver.o person-odb.o person-odb-mysql.o \ person-odb-pgsql.o -lodb-mysql -lodb-pgsql -lodb

Here is how we can access a MySQL database:

mysql --user=odb_test --database=odb_test < person-mysql.sql ./driver mysql --user odb_test --database odb_test

Or a PostgreSQL database:

psql --user=odb_test --dbname=odb_test -f person-pgsql.sql ./driver pgsql --user odb_test --database odb_test

2.11 Summary

This chapter presented a very simple application which, nevertheless,

exercised all of the core database functions: persist(),

query(), load(), update(),

and erase(). We also saw that writing an application

that uses ODB involves the following steps:

- Declare persistent classes in header files.

- Compile these headers to generate database support code.

- Link the application with the generated code and two ODB runtime libraries.

Do not be concerned if, at this point, much appears unclear. The intent of this chapter is to give you only a general idea of how to persist C++ objects with ODB. We will cover all the details throughout the remainder of this manual.

3 Working with Persistent Objects

The previous chapters gave us a high-level overview of ODB and

showed how to use it to store C++ objects in a database. In this

chapter we will examine the ODB object persistence model as

well as the core database APIs in greater detail. We will

start with basic concepts and terminology in Section

3.1 and Section 3.3 and continue with the

discussion of the odb::database class in

Section 3.4, transactions in

Section 3.5, and connections in

Section 3.6. The remainder of this chapter

deals with the core database operations and concludes with

the discussion of ODB exceptions.

In this chapter we will continue to use and expand the

person persistent class that we have developed in the

previous chapter.

3.1 Concepts and Terminology

The term database can refer to three distinct things: a general notion of a place where an application stores its data, a software implementation for managing this data (for example MySQL), and, finally, some database software implementations may manage several data stores which are usually distinguished by name. This name is also commonly referred to as a database.

In this manual, when we use the word database, we

refer to the first meaning above, for example,

"The update() function saves the object's state to

the database." The term Database Management System (DBMS) is

often used to refer to the second meaning of the word database.

In this manual we will use the term database system

for short, for example, "Database system-independent

application code." Finally, to distinguish the third meaning

from the other two, we will use the term database name,

for example, "The second option specifies the database name

that the application should use to store its data."

In C++ there is only one notion of a type and an instance

of a type. For example, a fundamental type, such as int,

is, for the most part, treated the same as a user defined class

type. However, when it comes to persistence, we have to place

certain restrictions and requirements on certain C++ types that

can be stored in the database. As a result, we divide persistent

C++ types into two groups: object types and value

types. An instance of an object type is called an object

and an instance of a value type — a value.

An object is an independent entity. It can be stored, updated, and deleted in the database independent of other objects. Normally, an object has an identifier, called object id, that is unique among all instances of an object type within a database. In contrast, a value can only be stored in the database as part of an object and doesn't have its own unique identifier.

An object consists of data members which are either values (Chapter 7, "Value Types"), pointers to other objects (Chapter 6, "Relationships"), or containers of values or pointers to other objects (Chapter 5, "Containers"). Pointers to other objects and containers can be viewed as special kinds of values since they also can only be stored in the database as part of an object. Static data members are not stored in the database.

An object type is a C++ class. Because of this one-to-one

relationship, we will use terms object type

and object class interchangeably. In contrast,

a value type can be a fundamental C++ type, such as

int or a class type, such as std::string.

If a value consists of other values, then it is called a

composite value and its type — a

composite value type (Section 7.2,

"Composite Value Types"). Otherwise, the value is

called simple value and its type — a

simple value type (Section 7.1,

"Simple Value Types"). Note that the distinction between

simple and composite values is conceptual rather than

representational. For example, std::string

is a simple value type because conceptually string is a

single value even though the representation of the string

class may contain several data members each of which could be

considered a value. In fact, the same value type can be

viewed (and mapped) as both simple and composite by different

applications.

While not strictly necessary in a purely object-oriented application,

practical considerations often require us to only load a

subset of an object's data members or a combination of members

from several objects. We may also need to factor out some

computations to the relational database instead of performing

them in the application's process. To support such requirements

ODB distinguishes a third kind of C++ types, called views

(Chapter 10, "Views"). An ODB view is a C++

class that embodies a light-weight, read-only

projection of one or more persistent objects or database

tables or the result of a native SQL query execution.

Understanding how all these concepts map to the relational model will hopefully make these distinctions clearer. In a relational database an object type is mapped to a table and a value type is mapped to one or more columns. A simple value type is mapped to a single column while a composite value type is mapped to several columns. An object is stored as a row in this table and a value is stored as one or more cells in this row. A simple value is stored in a single cell while a composite value occupies several cells. A view is not a persistent entity and it is not stored in the database. Rather, it is a data structure that is used to capture a single row of an SQL query result.

Going back to the distinction between simple and composite values, consider a date type which has three integer members: year, month, and day. In one application it can be considered a composite value and each member will get its own column in a relational database. In another application it can be considered a simple value and stored in a single column as a number of days from some predefined date.

Until now, we have been using the term persistent class to refer to object classes. We will continue to do so even though a value type can also be a class. The reason for this asymmetry is the subordinate nature of value types when it comes to database operations. Remember that values are never stored directly but rather as part of an object that contains them. As a result, when we say that we want to make a C++ class persistent or persist an instance of a class in the database, we invariably refer to an object class rather than a value class.

Normally, you would use object types to model real-world entities,

things that have their own identity. For example, in the

previous chapter we created a person class to model

a person, which is a real-world entity. Name and age, which we

used as data members in our person class are clearly

values. It is hard to think of age 31 or name "Joe" as having their

own identities.

A good test to determine whether something is an object or a value, is to consider if other objects might reference it. A person is clearly an object because it can be referred to by other objects such as a spouse, an employer, or a bank. On the other hand, a person's age or name is not something that other objects would normally refer to.

Also, when an object represents a real entity, it is easy to choose a suitable object id. For example, for a person there is an established notion of an identifier (SSN, student id, passport number, etc). Another alternative is to use a person's email address as an identifier.

Note, however, that these are only guidelines. There could

be good reasons to make something that would normally be

a value an object. Consider, for example, a database that

stores a vast number of people. Many of the person

objects in this database have the same names and surnames and

the overhead of storing them in every object may negatively

affect the performance. In this case, we could make the first name

and last name each an object and only store pointers to

these objects in the person class.

An instance of a persistent class can be in one of two states: transient and persistent. A transient instance only has a representation in the application's memory and will cease to exist when the application terminates, unless it is explicitly made persistent. In other words, a transient instance of a persistent class behaves just like an instance of any ordinary C++ class. A persistent instance has a representation in both the application's memory and the database. A persistent instance will remain even after the application terminates unless and until it is explicitly deleted from the database.

3.2 Declaring Persistent Objects and Values

To make a C++ class a persistent object class we declare

it as such using the db object pragma, for

example:

#pragma db object

class person

{

...

};

The other pragma that we often use is db id

which designates one of the data members as an object id, for

example:

#pragma db object

class person

{

...

#pragma db id

unsigned long long id_;

};

The object id can be of a simple or composite (Section

7.2.1, "Composite Object Ids") value type. This type should be

default-constructible, copy-constructible, and copy-assignable. It

is also possible to declare a persistent class without an object id,

however, such a class will have limited functionality

(Section 14.1.6, "no_id").

The above two pragmas are the minimum required to declare a persistent class with an object id. Other pragmas can be used to fine-tune the database-related properties of a class and its members (Chapter 14, "ODB Pragma Language").

Normally, a persistent class should define the default constructor. The

generated database support code uses this constructor when

instantiating an object from the persistent state. If we add the

default constructor only for the database support code, then we

can make it private provided we also make the odb::access

class, defined in the <odb/core.hxx> header, a

friend of this object class. For example:

#include <odb/core.hxx>

#pragma db object

class person

{

...

private:

friend class odb::access;

person () {}

};

It is also possible to have an object class without the default constructor. However, in this case, the database operations will only be able to load the persistent state into an existing instance (Section 3.9, "Loading Persistent Objects", Section 4.4, "Query Result").

The ODB compiler also needs access to the non-transient

(Section 14.4.11, "transient")

data members of a persistent class. The ODB compiler can access

such data members directly if they are public. It can also do

so if they are private or protected and the odb::access

class is declared a friend of the object type. For example:

#include <odb/core.hxx>

#pragma db object

class person

{

...

private:

friend class odb::access;

person () {}

#pragma db id

unsigned long long id_;

std::string name_;

};

If data members are not accessible directly, then the ODB

compiler will try to automatically find suitable accessor and

modifier functions. To accomplish this, the ODB compiler will

try to lookup common accessor and modifier names derived from

the data member name. Specifically, for the name_

data member in the above example, the ODB compiler will look

for accessor functions with names: get_name(),

getName(), getname(), and just

name() as well as for modifier functions with

names: set_name(), setName(),

setname(), and just name(). You can

also add support for custom name derivations with the

--accessor-regex and --modifier-regex

ODB compiler options. Refer to the

ODB

Compiler Command Line Manual for details on these options.

The following example illustrates automatic accessor and modifier

discovery:

#pragma db object

class person

{

public:

person () {}

...

unsigned long long id () const;

void id (unsigned long long);

const std::string& get_name () const;

std::string& set_name ();

private:

#pragma db id

unsigned long long id_; // Uses id() for access.

std::string name_; // Uses get_name()/set_name() for access.

};

Finally, if a data member is not directly accessible and the

ODB compiler was unable to discover suitable accessor and

modifier functions, then we can provide custom accessor

and modifier expressions using the db get

and db set pragmas. For more information

on custom accessor and modifier expressions refer to

Section 14.4.5,

"get/set/access".

Data members of a persistent class can also be split into separately-loaded and/or separately-updated sections. For more information on this functionality, refer to Chapter 9, "Sections".

You may be wondering whether we also have to declare value types

as persistent. We don't need to do anything special for simple value

types such as int or std::string since the

ODB compiler knows how to map them to suitable database types and

how to convert between the two. On the other hand, if a simple value

is unknown to the ODB compiler then we will need to provide the

mapping to the database type and, possibly, the code to

convert between the two. For more information on how to achieve

this refer to the db type pragma description

in Section 14.3.1, "type".

Similar to object classes, composite value types have to be

explicitly declared as persistent using the db value

pragma, for example:

#pragma db value

class name

{

...

std::string first_;

std::string last_;

};

Note that a composite value cannot have a data member designated as an object id since, as we have discussed earlier, values do not have a notion of identity. A composite value type also doesn't have to define the default constructor, unless it is used as an element of a container. The ODB compiler uses the same mechanisms to access data members in composite value types as in object types. Composite value types are discussed in more detail in Section 7.2, "Composite Value Types".

3.3 Object and View Pointers

As we have seen in the previous chapter, some database operations

create dynamically allocated instances of persistent classes and

return pointers to these instances. As we will see in later chapters,

pointers are also used to establish relationships between objects

(Chapter 6, "Relationships") as well as to cache

persistent objects in a session (Chapter 11,

"Session"). While in most cases you won't need to deal with

pointers to views, it is possible to a obtain a dynamically allocated

instance of a view using the result_iterator::load()

function (Section 4.4, "Query Results").

By default, all these mechanisms use raw pointers to return

objects and views as well as to pass and cache objects. This

is normally sufficient for applications

that have simple object lifetime requirements and do not use sessions

or object relationships. In particular, a dynamically allocated object

or view that is returned as a raw pointer from a database operation

can be assigned to a smart pointer of our choice, for example

std::auto_ptr (C++98/03 only), std::unique_ptr

from C++11, or shared_ptr from C++11 or Boost.

However, to avoid any possibility of a mistake, such as forgetting

to use a smart pointer for a returned object or view, as well as to

simplify the use of more advanced ODB functionality, such as sessions

and bidirectional object relationships, it is recommended that you use

smart pointers with the sharing semantics as object pointers.

The shared_ptr smart pointer from C++11 or Boost

is a good default choice. However, if sharing is not required and

sessions are not used, then std::unique_ptr or

std::auto_ptr can be used just as well.

ODB provides several mechanisms for changing the object or view pointer

type. To specify the pointer type on the per object or per view basis

we can use the db pointer pragma, for example:

#pragma db object pointer(std::shared_ptr)

class person

{

...

};

We can also specify the default pointer for a group of objects or views at the namespace level:

#pragma db namespace pointer(std::shared_ptr)

namespace accounting

{

#pragma db object

class employee

{

...

};

#pragma db object

class employer

{

...

};

}

Finally, we can use the --default-pointer option to specify

the default pointer for the whole file. Refer to the

ODB

Compiler Command Line Manual for details on this option's argument.

The typical usage is shown below:

--default-pointer std::shared_ptr

An alternative to this method with the same effect is to specify the default pointer for the global namespace:

#pragma db namespace() pointer(std::shared_ptr)

Note that we can always override the default pointer specified

at the namespace level or with the command line option using

the db pointer object or view pragma. For

example:

#pragma db object pointer(std::shared_ptr)

namespace accounting

{

#pragma db object

class employee

{

...

};

#pragma db object pointer(std::unique_ptr)

class employer

{

...

};

}

Refer to Section 14.1.2, "pointer

(object)", Section 14.2.4, "pointer

(view)", and Section 14.5.1, "pointer

(namespace)" for more information on these mechanisms.

Built-in support that is provided by the ODB runtime library allows us

to use std::shared_ptr (C++11),

std::unique_ptr (C++11), or std::auto_ptr

(C++98/03 only) as pointer types. Plus, ODB profile libraries, that are

available for commonly used frameworks and libraries (such as Boost and

Qt), provide support for smart pointers found in these frameworks and

libraries (Part III, "Profiles"). It is also easy to

add support for our own smart pointers, as described in

Section 6.5, "Using Custom Smart Pointers".

3.4 Database

Before an application can make use of persistence services

offered by ODB, it has to create a database class instance. A

database instance is the representation of the place where

the application stores its persistent objects. We create

a database instance by instantiating one of the database

system-specific classes. For example, odb::mysql::database

would be such a class for the MySQL database system. We will

also normally pass a database name as an argument to the

class' constructor. The following code fragment

shows how we can create a database instance for the MySQL

database system:

#include <odb/database.hxx>

#include <odb/mysql/database.hxx>

unique_ptr<odb::database> db (

new odb::mysql::database (

"test_user" // database login name

"test_password" // database password

"test_database" // database name

));

The odb::database class is a common interface for

all the database system-specific classes provided by ODB. You

would normally work with the database

instance via this interface unless there is a specific

functionality that your application depends on and which is

only exposed by a particular system's database

class. You will need to include the <odb/database.hxx>

header file to make this class available in your application.

The odb::database interface defines functions for

starting transactions and manipulating persistent objects.

These are discussed in detail in the remainder of this chapter

as well as the next chapter which is dedicated to the topic of

querying the database for persistent objects. For details on the

system-specific database classes, refer to

Part II, "Database Systems".

Before we can persist our objects, the corresponding database schema has to be created in the database. The schema contains table definitions and other relational database artifacts that are used to store the state of persistent objects in the database.

There are several ways to create the database schema. The easiest is to

instruct the ODB compiler to generate the corresponding schema from the

persistent classes (--generate-schema option). The ODB

compiler can generate the schema as a standalone SQL file,

embedded into the generated C++ code, or as a separate C++ source file

(--schema-format option). If we are using the SQL file

to create the database schema, then this file should be executed,

normally only once, before the application is started.

Alternatively, if the schema is embedded directly into the generated

code or produced as a separate C++ source file, then we can use the

odb::schema_catalog class to create it in the database

from within our application, for example:

#include <odb/schema-catalog.hxx> odb::transaction t (db->begin ()); odb::schema_catalog::create_schema (*db); t.commit ();

Refer to the next section for information on the

odb::transaction class. The complete version of the above

code fragment is available in the schema/embedded example in

the odb-examples package.

The odb::schema_catalog class has the following interface.

You will need to include the <odb/schema-catalog.hxx>

header file to make this class available in your application.

namespace odb

{

class schema_catalog

{

public:

static void

create_schema (database&,

const std::string& name = "",

bool drop = true);

static void

drop_schema (database&, const std::string& name = "");

static bool

exists (database_id, const std::string& name = "");

static bool

exists (const database&, const std::string& name = "")

};

}

The first argument to the create_schema() function

is the database instance that we would like to create the schema in.

The second argument is the schema name. By default, the ODB

compiler generates all embedded schemas with the default schema

name (empty string). However, if your application needs to

have several separate schemas, you can use the

--schema-name ODB compiler option to assign

custom schema names and then use these names as a second argument

to create_schema(). By default, create_schema()

will also delete all the database objects (tables, indexes, etc.) if

they exist prior to creating the new ones. You can change this

behavior by passing false as the third argument. The

drop_schema() function allows you to delete all the

database objects without creating the new ones.

If the schema is not found, the create_schema() and

drop_schema() functions throw the

odb::unknown_schema exception. You can use the

exists() function to check whether a schema for the

specified database and with the specified name exists in the

catalog. Note also that the create_schema() and

drop_schema() functions should be called within a

transaction.